Health

In Memory of the Spanish Flu

The origins of the virus are disputed. Researchers have pointed to China, Austria and France.

A hundred years ago the First World War was lurching bloodily towards its squalid end. The Germans were planning their Spring Offensive: a desperate attempt to beat the Allies before the Americans could intervene. Its failure led grindingly to their defeat. An Allied counteroffensive smashed the Hindenberg Line, General Ludendorff endured something close to a breakdown and the Germans slowly, sullenly began to surrender.

I would argue that the First World War was the most important episode of the 20th Century. The Tsar’s bad joke of a campaign fuelled the rise of communism. Germans, humiliated and impoverished at Versailles, were left to stew in the resentment that inspired Nazism. The British, who had lost almost three quarters of a million men in a war many had expected to be won in months, had been devastated militarily and psychologically. The French had lost a million men. Europe was not the same.

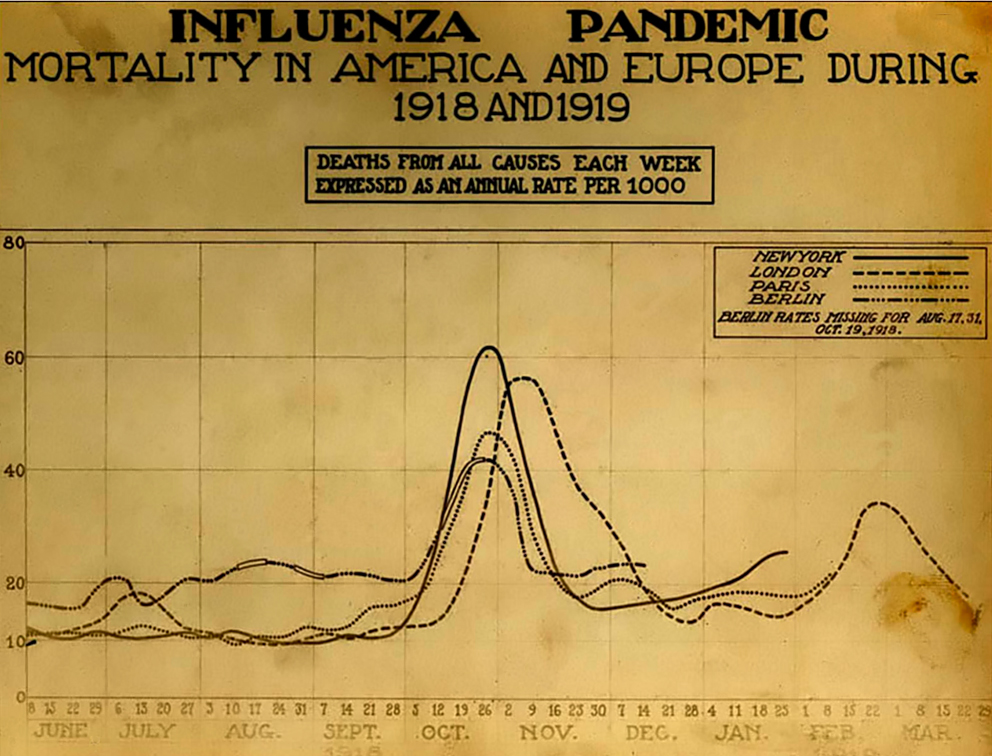

Even as the war began to end, however, and as people might have been excused for breathing sighs of relief, the world was stumbling into the arms of another catastrophe. Months earlier, in 1917, an aggressive virus had begun to spread through military camps in Europe and the United States. As troops marched between neighbourhoods, and between nations, sneezes and coughs passed this virus onto local populations. As people began to die, wartime censorship ensured reports of this strange, alarming illness were stifled. Neutral Spain was allowed to be reported on, however, so as Spaniards, including King Alfonso, were stricken, the pandemic was erroneously named “the Spanish Flu.”

The origins of the virus are disputed. Researchers have pointed to China, Austria and France. What is indisputable is that wartime conditions—with millions of malnourished men being herded together and sent across borders and over oceans—enabled its spread. In a matter of weeks, millions from England to Ethiopia had been taken sick, and had weakened, and had died.

Previously, influenza had been especially lethal when it had affected the young and the old. Now, all men, women, boys and girls were endangered. Research has suggested that a “cytokine storm,” caused by an overly severe response from the immune system, made a healthy person as if not more vulnerable than a weak one.

It is estimated that fifty to a hundred million people—three to six percent of the world’s population—died. No nation was safe, and some were devastated. SS Talune, a New Zealander ship, made a voyage so fatal that it dwarfed that of Titanic when it introduced the virus to Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Nauru. It is thought that 22% of the Western Samoan population died.

It was a horrifically lethal illness, and it was horrifically painful. Patients ached all over and coughed blood from ragged lungs. “Later,” one physician wrote to his friend, “You can begin to see the cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white.” “Two of them were married,” wrote one nurse of the soldiers she was busily treating, “And called out for their wife nearly all the time. It was sure pitiful to watch them die.”

It was painful for communities as well as individuals. Neighbourhoods and villages had already endured the loss of young men in the war. Now death was on their doorsteps. One man visited his ill sister and, on returning, was reported to have said:

My sister was already buried, but I was in time to bury father and mother, two other sisters, five people next door and view thirty-three funerals on the way to the railroad station.

Brevig Mission, in Alaska, was a little town with eighty inhabitants. In five days, seventy two of them were taken ill and died.

* * *

This essay, I must admit, has inauspicious origins. Last week, a Twitter account purportedly run by the British veteran and left-wing commentator Harry Leslie Smith published a tweet sarcastically wondering if Britain’s Conservative government would commemorate the Spanish Flu pandemic alongside its “mawkish” commemoration of the First World War.

I thought this reductionist and disrespectful, and said so, but my father replied that while the comparison was inapt, the pandemic deserves to be remembered. He was right.

It deserves to be remembered not just because of its magnitude–though there is that–but because of its relevance. We commemorate not solely to pay homage to the dead but to learn the lessons of their lives. We commemorate the war and think about the courage and sacrifice of the soldiers, as well, in my opinion, as the immense risks of statecraft and the need to seek de-escalation and diplomacy. Spanish Flu cries out for commemoration because of the millions who died and because of the millions who could die in the future. We have not eliminated the risk of pandemics. We are, in fact, in some ways making ourselves more vulnerable to them.

I have no wish to be alarmist. The world has coped with diseases since the Spanish Flu. SARS prompted a World Health Organisation global alert and effective international reactions minimised its spread. Ebola killed thousands in the recent epidemic but efficient governmental responses, especially admirable in underdeveloped African states, helped us avoid catastrophe. David M. Morens, M.D., and Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said, “Almost all ‘then-versus now’ comparisons in theory are encouraging.”

Yet there are still reasons for concern. We are better prepared for infectious diseases, but there are more of them. A 2009 Nature study found that emerging infectious disease events “have risen significantly over time after controlling for reporting bias.”

Modern life, in some senses, exposes us to harm. Karen Starko has suggested that some of the deaths attributed to influenza may in fact have been results of aspirin overdoses. As the disease was rampaging across the Earth, Bayer, the pharmaceutical company which produced aspirin, was marketing its product fiercely and uncritically. Aspirin overdose produces flu-like symptoms and may have been destructive.

In our age, we face overprescription of a different kind. Antibiotic overuse is dangerous not just to the individual consumer but society at large. The National Institutes of Health press release that covered Morens and Fauci’s work mentioned “antibiotics effective against bacteria that cause influenza-associated pneumonia” as cause for optimism. Antibiotic misuse, on humans and animals, encourages antibiotic resistance. As ridiculously irresponsible as it is that antibiotics are still prescribed for illnesses they are not fit to treat, such as the common cold, it is outrageously absurd that they are still used in large quantities on farm animals. As Jonny Anomoly wrote for Quillette:

On factory farms, once new resistant strains of bacteria emerge, they are passed along to farmers who work with animals, workers who slaughter animals, consumers who eat meat, and people in the more general environment.

A World Health Organization report from 2014 concluded, “This serious threat is no longer a prediction for the future, it is happening right now…and has the potential to affect anyone, of any age, in any country.”

Rising populations, and increased urbanisation, exacerbates pandemic risk. People live in close proximity to each other, and to large amounts of animals, in often dangerously unsanitary conditions. Global travel can spread viruses and bacteria that develop. As third world populations rise, and as millions migrate, this is a threat to bear in mind. Larry Brilliant, physician and epidemiologist, has theorised that climate change could be a “Great Exacerbator”: driving human and animal populations together to “exchange new viruses.”

As cheering as it is that SARS, bird flu, and ebola were contained—and as much as that containment should quell paranoia—it does not excuse complacence. “Persuading members of the public or governments to keep the surveillance networks strong is an ongoing and crucial task,” wrote Alok Jha for the Guardian in 2013, before quoting Mark Woolhouse, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh: “This is one of those investments that, if it’s working, no one notices.”

So Harry Leslie Smith, whatever his intentions, and however bad his phrasing, was more right than me. It is good that we commemorate conflicts but we should remember different events as well; events that might not have such great dramatic qualities but that caused pain, and inspired virtue, and have implications for our lives. War appeals to our imagination, with its vivid, Manichean scenarios. Faceless viruses and bacteria killing anyone, anywhere do not make such good stories. Even fictional portrayals of pandemics, from I Am Legend to World War Z, depict diseases turning humans into monsters, not just corpses. To confront dangerous, invisible entities of our future we must compensate for our imaginative limits.